Communication Disorder: Diagnostic Criteria

A Communication disorder can be broadly defined, and may have multiple presentations involving difficulties with reception, production, processing, or comprehension, of verbal or written communication. It can be defined in terms of severity from mild to profound, may be first apparent in childhood, with genetic etiology, or acquired through environmental influences at any point in development (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2014).

Some are normal variations in language, which the clinician must take care not to pathologize. As with all DSM-5 disorders, the basic criteria of at least some degree of functional impairment in a major life area, and distress must be exhibited.

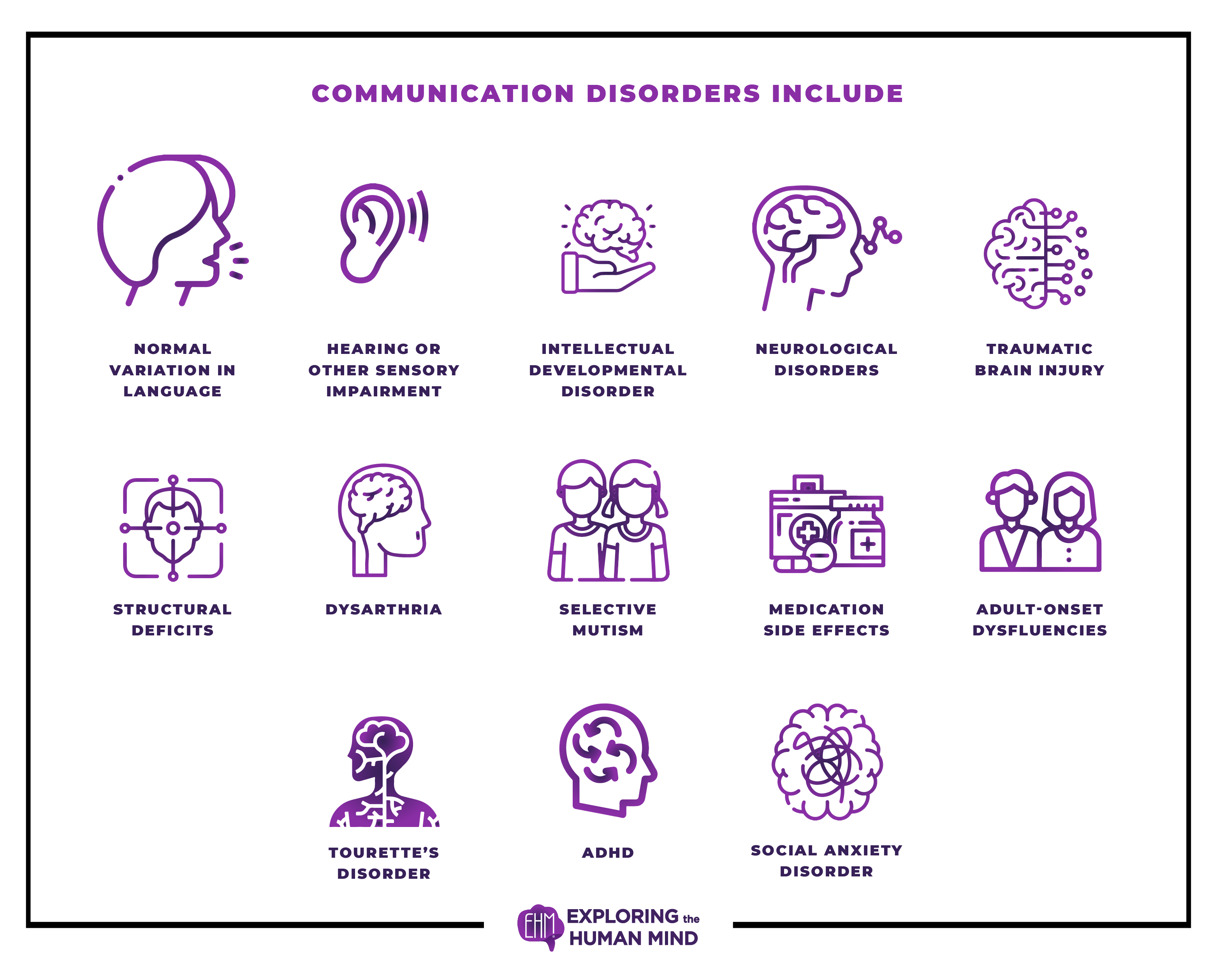

Communication disorders include:

Normal variations in language: There are normal variations in language that can be linked to one’s accent, based on geographic location or origin. Words in one language are filtered through another, and pronounced differently according to regional norms. For example, in Northern Vermont, the word Time is often pronounced with an “Oy” sound in the middle, due to filtering through French, whereas in neighboring upstate New York State, the same word is pronounced with an “Eye” sound. Contractions specific to a region may also be employed. A common affirmative in New England is “Ah-yep”, meaning, Ah, yes.

Hearing or other sensory impairment:

Hearing impairment is a possible rule-out for a communication disorder, as are other sensory or motor deficits than can interfere with productive or receptive speech.

Intellectual disability (Intellectual developmental disorder):

A delay in productive speech or difficulty comprehending receptive speech can be an expression of an intellectual disability.

Neurological disorders:

A Communication disorder can develop due to neurological disorders, including epilepsy syndrome.

TBI (Traumatic Brain injury):

Acquired deficits in productive or receptive speech can result from a TBI effecting Broca’s or Wernicke’s areas, respectively. This would not be classified as a communication disorder, as it is not of a neurodevelopmental nature.

Structural deficits:

Productive Speech can be impaired due to maxilla -facial structural defects, such a cleft palate.

Dysarthria:

Productive Speech impairment can be attributed to a motor disorder, such as CP (Cerebral Palsy).

Selective mutism:

Children - as well as adults or older teens - may not speak under certain circumstances secondary to anxiety, angry refusal to communicate, or as a deliberate passive-aggressive behavior.

Medication side effects:

Impairment of productive speech can be attributed to a side effect of a medication, as can difficulty comprehending receptive speech due to medication induced cognitive impairment.

Adult-onset dysfluencies:

If the onset of a productive speech disorder occurs during or after the teen years, is diagnosable as an Adult-onset communication disorder, rather than a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Tourette’s disorder:

Gille de Tourette’s syndrome involves phonic tics that are of a different quality than the diagnostic features of a communication disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder:

AD/HD may manifest as problems in communication due to inattentiveness. The causality is complex, in that a child may have AD/HD independent of symptoms of any type of communication disorder, including UCD. AD/HD is part of the spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders associated with Communication disorders, AD/HD is also identified as being causal, or as an exacerbating factor in communication disorders, due to impaired or delayed acquisition of reading and writing skills (St. Pourcain, Mandy, Heron, Golding, Smith, and Skuse, 2011)

Social anxiety disorder (social phobia):

The diagnostic features of social communication disorder overlap with the symptoms of social anxiety disorder, but are differentiated in that there is no history of normal social communication in the former (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Prognosis of Unspecified Communication Disorder

The diagnostic features of social communication disorder overlap with the symptoms of social anxiety disorder, but are differentiated in that there is no history of normal social communication in the former (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Reference:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (5th Edition). Washington, DC.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (1993). Definitions of communication disorders and variations [Relevant Paper]. Retrieved November 1, 2014 from www.asha.org/policy.

Krakowiak, P., Walker, C.K., Bremer, A.A., Baker, A.S., Ozonoff, S., Hansen, R.L., and Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2012). Maternal Metabolic Conditions and Risk for Autism and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Pediatrics.129 (5). 1121 -1128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2583.

Nichols, J.C. (2013). ICD -10: Specified or Unspecified. Health Data Consulting. Retrieved October 16, 2014 from http://humanservices.arkansas.gov/director/Documents/Unspecified%20Codes%20.%20Dr.%20Nichs.pdf

St. Pourcain, B., Mandy, W.P., Heron, J., Golding, J., Smith, G.D., and Skuse, D.H. (2011). Links Between Co-occurring Social-Communication and Hyperactive-Inattentive Trait Trajectories. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 50, (9). 892–902.e5 DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.015

Toppelberg, C.O. (2014). Do Language Disorders in Childhood Seal the Mental Health Fate of Grownups? Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1050 www.jaacap.org 53. (10).

Comments

Post a Comment